The Trader’s Original Sin Is Attempting To Make An Infinite Process Finite

Node 001 | The Index

The Idea INDEX

Node 001. (This Entry May Evolve)

First Published: 20.6.2025

This is a public work in progress.

An evolving index of links, notes, observations, and narrative fragments left to incubate, accumulate, and sometimes collide. The Idea Index Explained Here.

There’s value here already, though incomplete. These entries may connect with past or future Asymmetrist pieces or remain spare parts, waiting. This node will evolve.

Take what you like. Please share, fork, reject, and build on it. However, please attribute it.

But most of all: collaborate with me! Comment below or write directly: bogdan@asymmetrist.com

Eventually, enough of these nodes will emerge into something more.

The Trader’s Original Sin Is Attempting To Make An Infinite Process Finite.

All success and failure, including the trader’s condition—the embedded flaw—begin and end here. Can we venture further upstream? Because all else flows from here.

Markets are a finite, unintentional attempt to reflect the world succinctly. Yet the world is infinite. And so a contradiction is borne. From Traders of Our Time: Navigating the Impossible Landscape (TOOT):

“At the very least, the market environment represents an endless process of digesting perpetual, novel information in a human, linear and finite way. Seemingly, in that very core of the market lies a conflict, a contradiction, a paradoxical twist. A ‘conflict between the finite and infinite,’ as he puts it.”1 2

Douglas Hofstadter is “he,” re-describing his “strange loop” in Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid (GEB). The loop is partly a nonlinear, nonhierarchical, entangled system or environment that can look at itself and change behaviour. Navigating through that system will keep surprising you with where you end up. That is what makes it “strange.” In GEB, Hofstadter argues that this self-referential feature—the environment looking back at itself—lets life emerge from non-life.

Consider markets a wonder of nature and a force. From (TOOT):

“[The market is] an attuned, adapting ‘intelligence’ that, at some level, could be recognised as one of humanity’s earliest unintentional attempts to create ‘life’ from non-life, a non-human entity that can tell you what it ‘thinks’—prices, the action, order flow—in real time, for example, if a central banker is denying the market’s perception of reality, ‘transitory’ repeated in the face of persistent, spiking inflation.”3

Further from TOOT:

“[The market is] complex, like a rainforest, and not complicated, like a racing car. It becomes a self-reinforcing, chaotic, fat-tailed environment of perpetual novelty in the throes of ‘adaptive behaviour’ between participants … a paradoxical, self-referencing shape where the future drives the present and the present drives the future … persistent change and novel behaviour emerge from this small kernel of operation. Contradiction is at the very heart of the markets. That is how they are made.”4

Humans and their tools are finite, limited by biology, time, and mental bandwidth. Tools are purpose-built and limited to a specific function or environment in a moment in time. Yet, for humans and their tools, the market is essentially infinite.

So, by necessity, the trader must be reductive, finite just enough—but no more.

Comprehension and navigation of an infinite environment require a finite instance and a reductive categorisation of data, activities, behaviours, routines, etc. This presents an unresolvable conflict—a seemingly entangled paradox—and dealing with it is the trader’s burden.

Being overly reductive, too bound by rules, and excessively systematic can result in filtering and parsing information through multiple intermediaries, creating too many layers of abstraction between the trader and the markets. Failure is counted in layers. Fragility is proportional to the scaffolding supporting these layers. Hubris is revealed in erecting a building around these layers to permit worship.

Masterful traders slice the infinite as little as possible. They don’t ‘pare it back to the essence’ because the essence is already present: the markets. Instead, they pare themselves back, as they are the excess. These traders approach things with a fresh perspective, observing the market directly rather than inferring and interpreting through learned strategies, fads, or “latest”-isms. Thus, however they achieve this, it cannot be predicted and is unique to them.

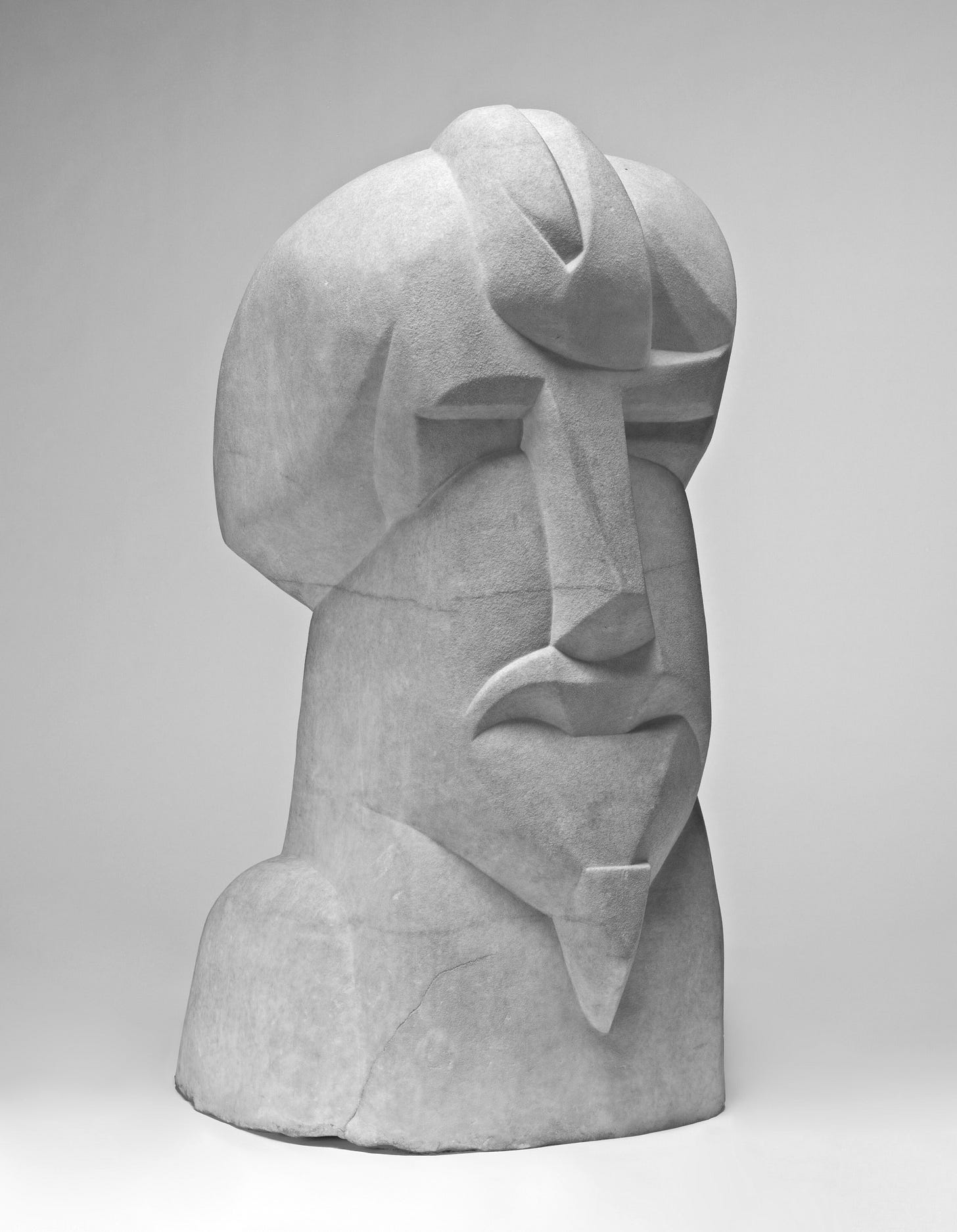

Find the equivalent of sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (HGB), identified by poet Ezra Pound in various writings—chiefly Pound’s Gaudier-Brzeska: A Memoir—who chiselled just enough to reveal the essence of the thing he is trying to represent. A modern return to pre-Antiquity where humans could infer and learn directly from the source and create art through their own talents: cave paintings, sculptures, etc., rather than following the mind-rails of a ‘school’ or ‘method’ with multiplied abstractions. HGB’s words:

“I shall derive my emotions solely from the arrangement of surfaces, I shall present my emotions by the arrangement of my surfaces, the planes and lines by which they are defined.”5

Consider HGB’s sculpture of Ezra Pound:

And consider:

In that moment, the artist—HGB—is defined by the phenomenon he directly observes when rendering something from a material, rather than working backwards to impose his static view. This shift occurred from Antiquity to the present: from observing first-hand to consuming third-hand. To eat from another’s principles instead of returning to first principles: direct to source. Consider The Sphinx from TOOT:

“It is a question of the level of detail. The first introduction and last conclusion of our trader is always, ‘I want to be formless in a market that has form.’ And everything flows downstream from there. ‘The market has a form, a structure, and a way of behaving and will do things according to its own rules. My place within it is to be a formless participant who does not have rules and a rigid structure. There is always a story in the markets and, day by day, things will construct themselves; you have to ask how your trading can fit within that story. Nothing else can come in between,’ The Sphinx continued. And to do that is to trade as close to the ‘market truth,’ the answer found in the language it speaks, that is, price, which we experience as order flow. Improvement begins and ends there.”6

How can so little express the maximum, or infinite? By taking the infinite and chiselling—reducing—it just enough and no more.

Consider Pound’s In a Station of the Metro:7

The apparition of these faces in the crowd; Petals on a wet, black bough.

Pound spent months writing a long poem about the Paris Metro but cut it down to two lines. It may look like he’s ‘cutting the fat’ or ‘paring it back to the essence’ but he found the essence, an image of natural life through direct observation and made it finite, reducing it, slicing infinity fourteen times and no more to render it comprehensible to us. That is the retention of essence through omission, why traders are defined by the trades they reject.

HGB’s sculptures and Pound’s poem are powerful because they require no scaffolding to be understood or rendered powerfully when we look, read and interact with them. They are timeless due to the lack of scaffolding, thus the fewest layers between their works and the infinity of life. You don’t need a ‘method’ or a ‘school’ to understand them. At the turn of the last century, HGB lamented this: “the architecture that would result would be quite original, new, primordial. A professional critic’s mind cannot see beyond vile revivals of Greco-Roman and Gothic styles.” This is also true when reviewing a masterful market navigator; there is tremendous depth because of their strength to omit. That’s why these traders seem unified, complete and brutally simple. That’s how they endure.

The least reductive wins, but achieving such intuitive, confident ability requires a deep, scrappy, meandering journey of failure, and consistent, grindy practice: immersion, immersion, immersion. Then, reflection, reflection, reflection, and return: “It is action that prepares you for reflection, and reflection that prepares you for action,” as explored in TOOT. 8

The least reductive wins because it permits incredible freedom of movement and expression. Trading is an act of creative courage, not computation. Traders with creative courage are dynamic, view the market holistically, yet think about the processes behind processes. What’s really going on? They’re more meta. Not: “What do I learn?” But: “How do I learn?” “How do I learn better ways to learn?” ‘What’ is transient. ‘How’ adapts to the now. It adapts to the world’s infinites and the markets. How makes you timeless yet dynamic enough to be on the cutting edge. Hence, Pound’s dictum: “Make It New.” (And the basis of: On Permanent Revolution.)

Pound composed his verse, and Gaudier-Brzeska sculpted as if they asked How do I make it? Not: What do I make?.

We return to the trader’s condition—the original sin—the fundamental flaw embedded into a market navigator because they are finite. A career is spent attempting to overcome what cannot be overcome. But that defines the trader. From TOOT:

“These acts of mastery conclude when a trader has to fight for their very conception, to struggle for it—to fight for expression against anything that might devour it. One great act of defiance. Magisterial careers, then, are born from continual resistance.” 9

Consider Chaucer grappling with the world’s infinity and the writer’s finality. Thus, we’re all summarised:

“The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne.”10

To Be Developed—Node 001 | The Index

Footnotes:

Traders of Our Time: Navigating the Impossible Landscape, by Bogdan Stoichescu and Alexander Haywood. Axia Trading Biblioteca, 2025.

Chapter 13: The Sphinx, subtitle: “It is I, The Market!”, p. 428 (European hardback edition).

“Conflict between the finite and infinite” is drawn from GEB (p. 15) — Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, by Douglas R. Hofstadter. Basic Books, 1999 paperback edition (ISBN 9780465026562). Note: pagination refers to the 1999 U.S. edition; other editions may vary.

Traders of Our Time, p. 438 (European hardback edition). Chapter 13: The Sphinx, subtitle: “It is I, The Market!”

Traders of Our Time, pp. 31–32 (European hardback edition). Preface: Thinking Upstream, subtitle: “Why Think Meta?”

Ezra Pound, Gaudier-Brzeska: A Memoir. London: John Lane; Bodley Head, 1916. p. 20.

Traders of Our Time, pp. 446-447 (European hardback edition). Chapter 13: The Sphinx, subtitle: “Truth”

Ezra Pound, In a Station of the Metro, in Early Writings (Pound, Ezra): Poems and Prose, ed. Ira B. Nadel. New York: Penguin Classics, 2005. p. 82.

Traders of Our Time, p. 249 (European hardback edition). Chapter 7: The Student, subtitle: “The Dual Tradition”

Traders of Our Time, p.60 (European hardback edition). Chapter 2: The Razor

Geoffrey Chaucer, The Parlement of Foules, quoted in Paul Johnson, Creators: From Chaucer and Dürer to Picasso and Disney, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2006. p. 23 (UK hardback edition).

Acknowledgements & Notice:

Image credit: Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound (1914), sculpture by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Public Domain. Retrieved Here.

To those unfamiliar with Ezra Pound, it should also be noted that, later in his life, he became a supporter of Mussolini, espoused Fascist ideology, and voiced antisemitic views. These aspects of his legacy remain deeply troubling and must be considered alongside his contributions to modernist literature. By no means should this discussion of Pound’s literary achievements be mistaken as casual support or endorsement of these views, either by the author or Asymmetrist